Today, Monday, March 8, people around the world have gathered to celebrate International Women’s Day. #IWD will be the number one trend on social media, there will be curated conversations and concerts around the importance of women, our strength , and calls for an equal world that will end at exactly midnight. This year’s theme is “Women in Leadership: achieving an equal future in a Covid-19 world’. Alongside this, is a social media campaign to encourage women to “#ChooseToChallenge and call out gender bias and inequality.

Gender bias and inequality has many faces. The manifestation that is all too familiar to all women is that of violence. Young women in Uganda have long resisted sexual violence in particular. The story of Rachel Njoroge portrays this resistance.

On April 13, 2018, Rachel Njoroge went to certify copies of her academic transcript at Makerere University. She entered Edward Kisuze’s office in Room 507 at Makerere University’s Senate Building. What followed was a violent incident that has from that day defined her life. Njoroge reported Edward Kisuze for forcibly grabbing her breasts, pushing her against the filing cabinets, and grabbing her hand which he brought to touch his penis. He proceeded to lower his head to her thighs, and started kissing them as he tried to remove her panties. She threatened to jump out of the 5th floor window of Edward Kisuze’s office before he stopped violating her.

She was courageous enough to take some pictures during this ordeal. Proof in hand, Njoroge rushed to the Makerere University administration office. There, she shared the images with their IT personnel who promised to handle the matter. They didn’t. A few days later, the images, evidence she had painstakingly collected, were leaked to a tabloid newspaper in Uganda. The source of this leak remains unnamed. True to Ugandan media’s portrayal of women’s experiences of sexual violence, Rachel was plastered all over tabloid pages. Meanwhile, Edward Kisuze’s actions remained far away from public scrutiny. The male sanctifying magic of media spin.

Feminist lawyer Twasiima Bigirwa in her paper; “Skewed Dynamics; Exploring Ways in Which Media Fuels Inequality in Uganda;” underscores the ways in which Ugandan media contributes to the normalization of sexist practices and beliefs by trivializing violence against women. Referring to the case against Brian Isiko which was reported as “love messages” rather than harassment, Twasiima concludes: “ The beliefs around the representations of relationships between women and men that depict women as objects in men’s sexual desires are as a result of cultural and religious conditioning, reinforced by media language choices in their reporting on cases such as the one above.” Rachel’s case was yet another example of the media’s complicity in this gendered sexual violence.

Rachel Njoroge sought justice in the courts of law. After a two year long court battle, the sitting Chief Magistrate at Buganda Road Court confirmed what she already knew: Edward Kisuze had sexually assaulted her. In a system as under-resourced as ours, Rachel had had to be very close to the prosecution to secure a conviction. Without enough human and financial resources for the system to serve justice, it was Rachel who would have to follow up the case file both at the court and at the Police station, ensuring that the witnesses showed up, and that they provided the evidence necessary for the case to be heard to its logical conclusion. She also endured harsh cross examination when she gave her own testimony, as if the humiliation she was facing in the public eye was not enough. When the accused was put on his defence, his victim was accused of only wanting to break up a man’s family.

Kisuze was acquitted of the charge of attempted rape. Instead, he was convicted on the lesser charge of “indecent assault” and sentenced to 2 years in prison or in the alternative, a meagre UGX 4,000,000 (about USD 1,000) to be paid to the court. He paid the amount that afternoon and went home a free man. A few weeks later, Kisuze appealed the sentence. To Rachel, it felt like a slap in the face.

The case decided against Edward Kisuze displays a big failure on the part of many of us who refuse to grasp the concept of consent; which in turn impedes our full conceptualisation of sexual assault and, or rape. The Chief Magistrate, after finding that Kisuze was indeed at the scene and rejecting his defence that claimed that Miss Njoroge had fainted, decided as follows:

“I have considered the evidence of prosecution, regarding the alleged attempted rape. However, the prosecution never adduced evidence to demonstrate that indeed there was an attempted sexual act manifested by the accused person in trying to insert his sexual organ into the victim…I agree with the defense in part. The evidence available does not show that the accused had gone to the extent of putting his intentions into execution.”

For clarity, the evidence referenced above and documented by the ruling of the appointment’s board of Makerere University during the at the discipline hearing included witnesses who had seen Miss Njoroge enter Kisuze’s office on that day, and Miss Njoroge’s sworn testimony that Kisuze had locked the door, forcibly kissed her thighs, tried to remove her underwear, and removed his penis which he tried to make her touch; before, penetrating her vagina with his fingers.

Criminal law can be summarised in this adage by an English jurist: “Better that ten guilty persons escape, than that one innocent suffer.” Also known as the presumption of innocence, it is the basis for placing the burden of proving that a crime was committed on the prosecution which is at a standard of “beyond reasonable doubt.” Unfortunately in cases of sexual violence, the burden placed the assaulted person is even heavier. They are asked to prove beyond reasonable doubt, not just the actions of their assaulter, but also that they had not given consent. In a world where women’s agency might as well be a myth; where societal belief is that a woman’s “no” means “yes”, women are disfavored from the onset.

A lawyer’s first instinct should be to look for ways to improve the system, to make it more gender-responsive, to enable women to report in better conditions. However, the numbers alone are discouraging – the 2019 Annual Police report indicated that of the 1,531 cases of rape recorded, only 20 were convicted, 6 acquitted and 15 discharged while 647 are still awaiting trial. This small success rate doesn’t inspire confidence in the system. When compounded by the stereotypical attitudes of many officials in the criminal justice system – from judges to prosecutors and even to police officers, faith in the system dwindles.

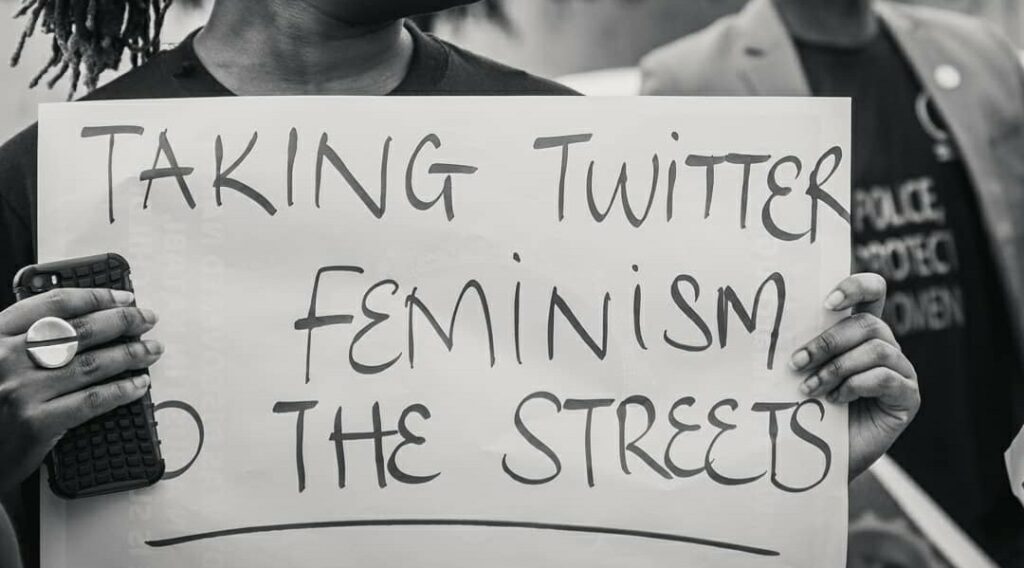

Feminist movements around the globe have emphasised that sexual violence happens on a continuum of violence against women, which is a part of a patriarchal system. In the 1977 “Letter to the Anti-Rape Movement” authored by the leaders of a group called the Santa Cruz Women Against Rape, it is clearly enunciated as follows: “We do not believe that rape can end within the present capitalist, racist, and sexist structure of our society. The fight against rape must be waged simultaneously with the fight against all other forms of oppression”. Women cannot continue to rely on the state funded system to do the work that only movements can do.

Feminist movements are tasked with organizing outside of the system to support survivors of sexual violence. Last year’s theme for the global #16DaysofActivism (the annual global campaign against sexual and other forms of violence against women focused on among others things, funding for sexual violence work. It would be a change of pace to see money and work put in alternatives to the criminal justice system like psychological support and creating communities of care for survivors.

In December 2020, Edward Kisuze was dismissed from Makerere University following his conviction in court in a disciplinary hearing that also condemned him to pay compensation to Rachel. The University also agreed to pay compensation to Rachel Njoroge. Still, the case put on full display the inadequacy of the legal system in dealing with cases of sexual violence, the pervasiveness of violence against women both online and offline, and the failure of our society to support victims of gender based violence.

What could we do differently to start to uproot this rotten system? First, we must commit to believe survivors of violence and to say it publically that we do. We must challenge the systems and cultures that allow violence to exist and thrive and we must do so constantly, not just on International Women’s Day. We must also create communities of care where survivors can find grace, healing, and where possible, mental health care. Femme Power Ug is a Ugandan collective of young women who are working to provide space for survivors of sexual assault. Many more collectives like this exist and deserve our financial and moral support so that survivors have a safe place to go when assaulted. Ultimately, we are each other’s business, and we must do more to protect and support each other, especially when we are dehumanised by patriarchal violence. Only then can we start to create a world where sexual violence is a thing of the past.